History of Parsi's

PARSIS IN 20TH CENTURY INDIA

The Industrial Revolution in 19th-century India had its impact on Gujarat with, for example, the building of cotton ginning factories in Broach. Most of the major developments, however, were in the city of Bombay, which gradually resulted in an increasing concentration of the Parsi community in the metropolis; however, at the start of the 20th century the majority of Parsis still lived elsewhere. A major force for change and migration had been the assumption of rule in India from the East India Company by the British Parliament and the Crown in 1858, after the Indian Mutiny. Although power rested ultimately with the company’s Court of Directors in London,

prior to 1857 effective influence was exercised by the people of India at a local level. It was knowledge of local or specialized trade (e.g., cotton) that gave individuals influence with the company. After 1857, influence had to be exerted in London on members of parliament, which meant that people had to be able to argue in Western terms that required, above all, a legal education. This national and international perspective gave increasing powers to the major conurbations such as Bombay, which prompted Parsis and others to move to these centers. The trend resulted in increasing urbanization, which also led to fragmentation as communities grew in new centers, such as Delhi and Karachi. This concentration on Bombay continued through the 20th century.

prior to 1857 effective influence was exercised by the people of India at a local level. It was knowledge of local or specialized trade (e.g., cotton) that gave individuals influence with the company. After 1857, influence had to be exerted in London on members of parliament, which meant that people had to be able to argue in Western terms that required, above all, a legal education. This national and international perspective gave increasing powers to the major conurbations such as Bombay, which prompted Parsis and others to move to these centers. The trend resulted in increasing urbanization, which also led to fragmentation as communities grew in new centers, such as Delhi and Karachi. This concentration on Bombay continued through the 20th century.

Migration to Bombay was mainly undertaken by young, active males with the result that rural communities increasingly consisted of the elderly and the disabled. The problem was exacerbated by some of the socialist policies of the government after Independence. First, under Mahatma Gandhi’s influence, prohibition was introduced, and, as most Parsis in Gujarat had made their living from the toddy production, many became unemployed. Landowners were restricted in what they could do with their land if they had tenant farmers, and further, defined by a list, to whom the option to buy should be given. A third factor was nationalization of public transport, a business many Parsis had turned to. As a result, from the late 1950s rural Parsis became increasingly impoverished (Shah, passim; Mistry, passim; Vajifda, passim; Marshal, passim; Bhaya, passim).

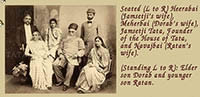

The picture painted is usually one of Parsi decline in the 20th century, but it must be borne in mind that from their Bombay base some Parsis, notably the Tatas and the Godrej families, exerted a major influence on the industrial revolution. The Tatas started India’s steel industry, and its major airline until it was nationalized, and donated considerable funds to scientific research in particular. Their political role and educational achievements have been discussed in the entry on Bombay. Parsis of India contributed substantially, in proportion to their numbers, to the British war effort in both World Wars, both through financial donations to equip the forces and in terms of lives lost.

In the 20th century, Parsis throughout India have shown an increasing interest in their own history. This began in the 1890s with the new building for Irān-šāh at Udwada. In the early years of the 20th century, roads and a dharmsala were built to cater for the growing number of pilgrims (Patel, pp. 471; Patel and Paymaster, IV, p. 3), and in 1921 a thanksgiving jašan was celebrated to mark the 1,200 year anniversary of the consecration of Irān-šāh (Patel and Paymaster, VI. p. 20). In 1917 the Bombay Parsi Panchayat agreed to fund a memorial column at Sanjān to commemorate the Parsis’ arrival in India. This was publicly unveiled in 1920, when three trainloads of Parsis came from Bombay and one from Surat. Additionally, large numbers came from surrounding villages to attend the public jašan and a dharmsala was built nearby for pilgrims.

This sense of history has been developed both by the large number of books about the community written from within, and by formal bodies and institutions that, although based in Bombay, have much wider influence. The monthly magazine Parsiana started in the 1960s but was taken over in the early 1970s and transformed into a professionally produced magazine that circulates among Parsi communities throughout India and the Diaspora. It includes articles on both religious and secular matters and periodically runs a series reproducing important earlier texts such as the judgment in the 1906 legal test case on intermarriage. Another Bombay based organization with both a national and an international role is Zoroastrian Studies, which was started in the 1970s by Khojeste P. Mistree, who had studied Zoroastrian studies at Oxford. Its primary function is to educate young Zoroastrians in their religion, but it also runs classes for adults and has become involved in wider policy issues, representing the Orthodox voice on such matters as intermarriage and funerals. It pioneered religious pilgrimages to Iran, and Mistree often visits diasporic communities, giving lectures and seminars.

In 1972 an umbrella body called “The Federation of Parsi Anjumans of India” was formed, linking all Parsi anjumans and panchayats throughout India. The ex-officio chairman is the chairman of the Bombay Parsi Panchayat with the chairs of Delhi and Calcutta as vice-chairs.

The aim was for the larger groups to support smaller anjumans in social concerns, but religious affairs are avoided in the hope of steering clear of dissension. The intention is to support smaller groups which do not have the resources to maintain properties. It has no effective powers but functions as a debating body.

The aim was for the larger groups to support smaller anjumans in social concerns, but religious affairs are avoided in the hope of steering clear of dissension. The intention is to support smaller groups which do not have the resources to maintain properties. It has no effective powers but functions as a debating body.

All the demographic studies of Indian Parsis report an aging and numerically diminishing community. With their high educational levels of achievement, and consequent success in professional lives, more Parsis, men and women alike, are postponing marriage or remaining single to pursue their chosen careers. The long-term problem of care for the elderly in the community causes concern, but the most contentious issue remains the acceptance of those who inter-marry and their spouses and offspring. Some argue that, unless they are accepted into the fold, the community will eventually die out, while others argue that intermarriage will erode the distinctiveness of the community. The disputes are extensive and bitter.

There are other contentious issues, notably regarding funerals. Where a daḵ-ma does not exist, then burial or cremation is accepted as necessary, but in the 1990s a virus destroyed the vulture population in Bombay.

There was fierce debate over possible alternatives. At first one group planned, with the aid of a veterinary specialist, to build a large aviary to breed vultures, but that proved impractical, costly, and vulnerable to the re-emergence of the virus. Solar panels have been tried to speed the decomposition of the body, but it seems that the ancient practice of exposing the dead is under threat in India.

The calendar debates, fuelled in the early 20th century by the introduction of the seasonal (faṣli) calendar which accords with the Gregorian, are not a matter of debate in India.

There was fierce debate over possible alternatives. At first one group planned, with the aid of a veterinary specialist, to build a large aviary to breed vultures, but that proved impractical, costly, and vulnerable to the re-emergence of the virus. Solar panels have been tried to speed the decomposition of the body, but it seems that the ancient practice of exposing the dead is under threat in India.

The calendar debates, fuelled in the early 20th century by the introduction of the seasonal (faṣli) calendar which accords with the Gregorian, are not a matter of debate in India.

One striking feature of Parsis in the 20th century is their increasing interaction with the diaspora. As more have migrated overseas, so the diaspora communities have grown in size, wealth, and influence. Parsi leaders travel to much of the diaspora, and overseas funds aid such projects as housing colonies in Navsari and the Parsi General Hospital in Bombay. Debates in the old country and the new world take on an international perspective in a way that was not the case before the 20th century.